At some point in time, most of us have probably heard of or had discussions about suspiciously wide-ranging permissions requested by consumer-oriented mobile apps.

An example could be a simple game or flashlight app requesting permissions to use your camera, view all of your files, access your contacts and even your location at all times. Why do these apps ask for these seemingly unnecessary permissions? In the consumer space, the intent can be malicious, but more often than not the apps seem to be oriented towards collecting data to sell it onward to third parties for monetary gain.

In the enterprise space (and in this case more specifically, in Entra ID) overly broad and unnecessary permission consent requests from apps can also be encountered. Entra ID apps asking for various permissions is a necessary mechanism to enable apps to integrate with the identity platform.

The trouble is that when app consents are unmanaged, they can also be a significant security risk considering that Microsoft’s default configuration for Entra ID is to allow any user to consent to any permission independently that doesn’t require something called Admin Consent – a separate ‘ok’ from a sufficiently entitled administrator identity.

Security researchers and security-focused blogs have been sounding the horn about the risks of unchecked multi-tenant app consents for years (see this demo from late 2018 for example) but it’s still all too common to encounter the default “open doors” settings and no monitoring even in environments with the licensing to do something about it.

A closer look

The risk of app consents is that once given, they by design can allow an attacker to take actions without a user’s knowledge and without requiring any interaction or credentials from the user. They can act both as a powerful reconnaissance and enumeration vector in the initial stage of an attack. When successfully used against user identities with elevated permissions, illicit app consent requests can also act as a more dangerous escalation towards control of entire tenants.

To really drive home the breadth of permissions users can consent to without triggering admin review of any kind, I cooked up the following example.

Here, our friend Joe Average working as a department manager for the fictional company Exolite just got a friendly email with a link attached and clicked it, leading him to the page below – possibly after first entering his credentials to the legitimate organizational login screen in Entra ID.

Take a look at what Joe is being asked to give permission to.

Even the most distracted and sleepy office worker would probably pause for more than a few moments when faced with a list of permissions such as this. In our case, Joe certainly looked at this one for a while and then decided to click cancel just to be sure, backing off from opening the doors wide to a third party with ill intentions.

If I sent such a consent request to a couple hundred of your colleagues, how many do you think would just scroll all the way down and click accept? Hopefully not a single one. Certainly not you, right?

The problem is, an actual illicit consent grant attack will be far more subtle. It might come from a spoofed email address resembling that of your company – or even from a coworker’s compromised account. It might be a link embedded into a fake newsletter containing topics relevant to the employee’s interests.. or any number of other cover stories.

Imagine that, instead of the gargantuan and strange prompt in the first example, Joe instead received an email from admin@ExoliteIT.com (not a real company domain, but close enough for the uninitiated) informing him of a new company drive to help cut down on pesky notification clutter in Teams by installing a custom-made assistant app for employees that will take care of all that automatically. Many casual users might be excited or at least interested in such a magical helper.

Joe certainly was, and clicked the included link, presenting him with this:

Joe was in a bit of a hurry to lunch so he took a quick look at the familiar Teams logo and a welcoming app name, saw the company’s name in the publisher field and glanced at the permissions, which didn’t really mean much to him. He shrugged, clicked Accept and took off for lunch. Somewhere else, the malicious intruder got to work.

No active monitoring for consent grants was in place so Exolite only picked up on the attack a good while later after the damage was already done and the attacker had leveraged Joe’s account to trick many of his colleagues into accepting similar requests, establishing persistence and allowing the attacker to then pivot towards spear-phishing privileged accounts.

The made-up Teams Assistant app here asks for consent to a collection of some the riskiest, most valuable Graph permissions a user can consent to independently. Real attacks could certainly mask their intent further by requesting less and more targeted permissions, by picking an even more specific app name using OSINT and reconnaissance done on the company and Joe beforehand etc. – all the classic tricks from the attacker’s phishing playbook can be used.

Now, some of you with Defender for Office 365 deployed might wonder: won’t malicious links like this get caught by Safe Links filtering?

Not necessarily. This is because permission consents for multi-tenant apps are a legitimate and necessary mechanism in Entra ID offered by Microsoft themselves. What to do about it then from a technical standpoint?

Many things, but you should start with three:

- Limit the ability of users to give consent to apps based on the risk level of each permission so only low-risk permissions can be consented to by users without separate admin consent.

- For any permissions not deemed low-risk enough for a user to consent to, make the user provide justification for why they (and possibly, their colleagues) need a given app. Then, make qualified admins look over the requests and determine whether the need is indeed legitimate.

- Identify risky apps that were already given consent by employees before controls were implemented and block them from the tenant using PowerShell, Defender for Cloud Apps or a mix of both.

In this article, we will look at how to take the first two of these steps towards managing app consents without just outright blocking them, which would naturally mitigate the risk but would also end up hindering legitimate productivity sooner or later.

For the third step, Microsoft already provides a high-quality playbook that I can happily recommend to anyone: App consent grant investigation | Microsoft Docs

Limit user app consents

Let’s navigate to the Azure portal at portal.azure.com and go to Azure Active Directory > Enterprise applications > Consent and permissions.

First, we will look at Permission classifications. Here, Microsoft proposes a set of five Graph permissions that are of a low enough risk that users should be OK consenting to by themselves. These include the ability to:

- Sign the user into an app using their Entra ID identity (openid)

- View the user’s email address (email)

- View the user’s profile and basic company information. For more on what exactly is returned with this permission, see the relevant documentation here. (User.read & profile)

- Maintain access to any information the app has access to through permission consent – even if the user is not using the app. It practically lets the app request and receive new refresh tokens, which in turn let the app request access tokens. These let the app independently access information the app has permissions to. (offline_access)

Offline_access is either low-risk or high-risk depending on the context. Coupled only with other low-risk permissions, it is pretty benign. On the other hand, coupled with something like Files.ReadWrite.All, it becomes very potent indeed.

Let’s classify the proposed five low-risk permissions as low-risk – a quick step-by-step guide can be found in Learn.

When this is done, we’ll switch over to look at User consent settings. There, we will set User consent for applications from the default value of Allow user consent for apps to our desired setting: Allow user consent for apps from verified publishers, for selected permissions. I think it is interesting that Microsoft actually recommend this setting even though it isn’t currently provided as the default.

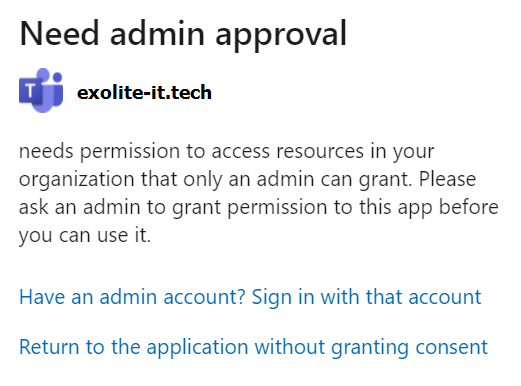

This in itself would ensure that Joe Average in our example scenario would not be able to just consent on his own the malicious Teams Assistant app. If he tried to navigate to the app consent link, he would see something like this:

Ok, first step taken. The situation still isn’t optimal though – the only way Joe could ask permissions for apps in this case would be to manually contact admins through some internal channel to present his business demand. To let Joe and others like him efficiently ask for legitimate permissions to data, we’ll need to implement one more feature.

Admin consent request workflow

The Entra ID admin consent workflow lets users request admin consent to apps that they would otherwise be unable to consent to by themselves. In our case, this means any apps requesting permissions we haven’t deemed as low-risk in the previous step.

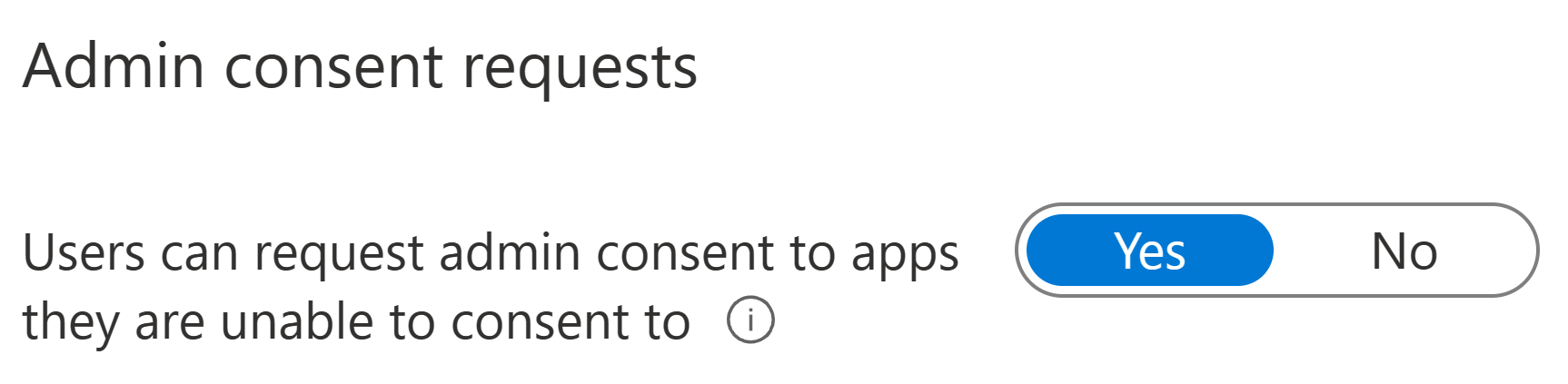

Enabling admin consent requests supports users in cases where there is a real need for an app with elevated permissions without taking away admin visibility to risky scenarios. In the Azure portal, we will naviate to Azure Active Directory > Enterprise Applications > User settings. Here, we will first turn on the admin consent request workflow and then get to specifying some details.

When enabling the workflow, we also need to decide who can review the requests made by users. We can specify this on the user-, group- or role level. Any user (privileged account or not) can review, block or deny admin consent requests. To actually grant admin consent to an app, you’ll need someone with Cloud application admin, Application admin or Global admin privileges. This is because an admin consent grant, when given, applies to the entire organization – not just for the initial user identity requesting the permission.

This, in turn, has the benefit of freeing admins from repeatedly approving already-approved app permissions, which is especially important to ensure that the solution scales well in organizations with hundreds, thousands or perhaps tens of thousands of people using the same app.

Tenant-wide app consent can also directly be requested for in a similar fashion to the user-level consent. In the case of multi-tenant apps, the admin consent request link would look like this:

https://login%5Bdot%5Dmicrosoftonline%5Bdot%5Dcom/common/adminconsent?client_id=

What I’m trying to say here is that admins need to be extra careful when consent request screens pop up. Identities with sufficient privileges to grant admin consent aren’t limited by the controls we implemented here to protect normal user identities.

After consent request reviewers are designated, we’ll need to choose a couple more things:

- Whether or not designated reviewers will get an email notification for admin consent requests.

- The expiration time for individual admin consent requests – can be between 1-60 days.

- Whether or not designated reviewers receive an email reminder close to the expiration date of an unhandled admin consent request.

With the admin consent workflow configured, let’s see how it affects Joe’s user experience:

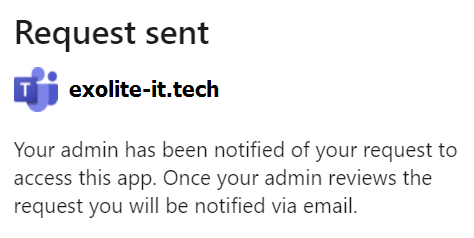

As we can see, Joe isn’t immediately allowed to consent to the permissions but can let the reviewers know why he thinks he needs the app. Let’s say our protagonist explains the email he got and hits Request approval – what happens next?

First off, if email notifications were configured for new admin consent requests, any designated reviewers will receive the following message:

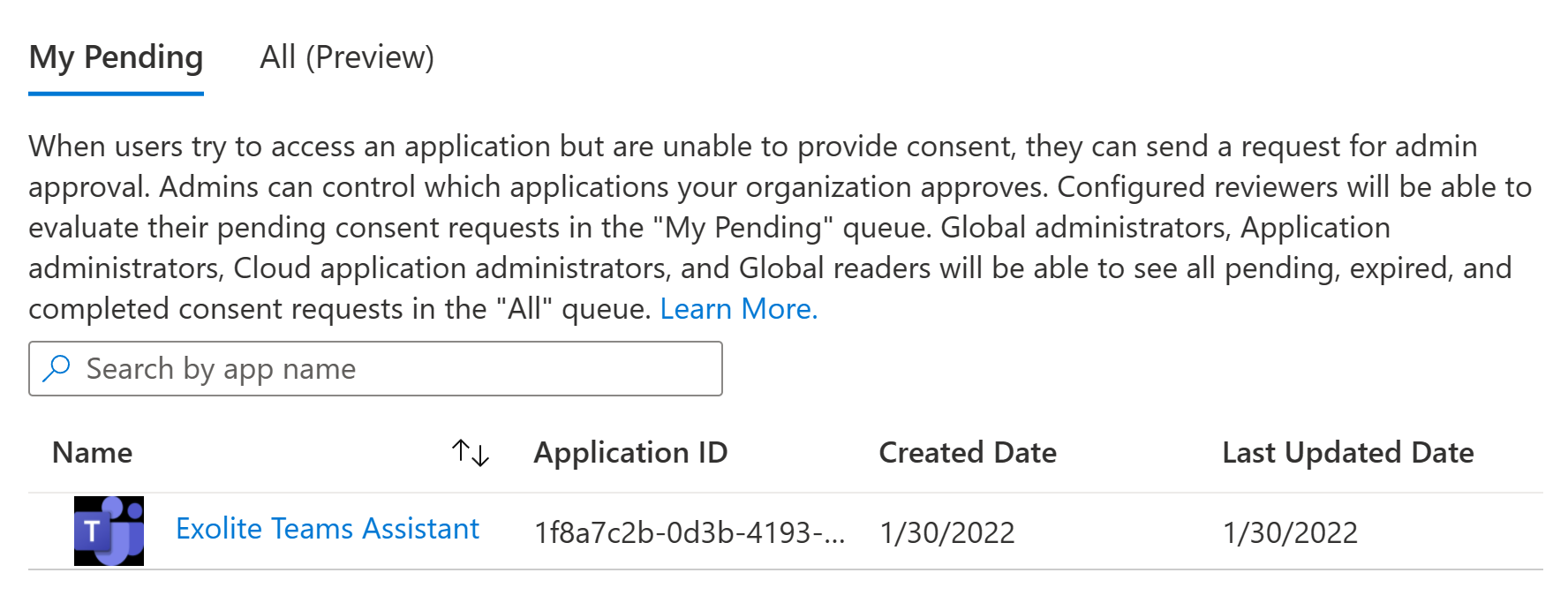

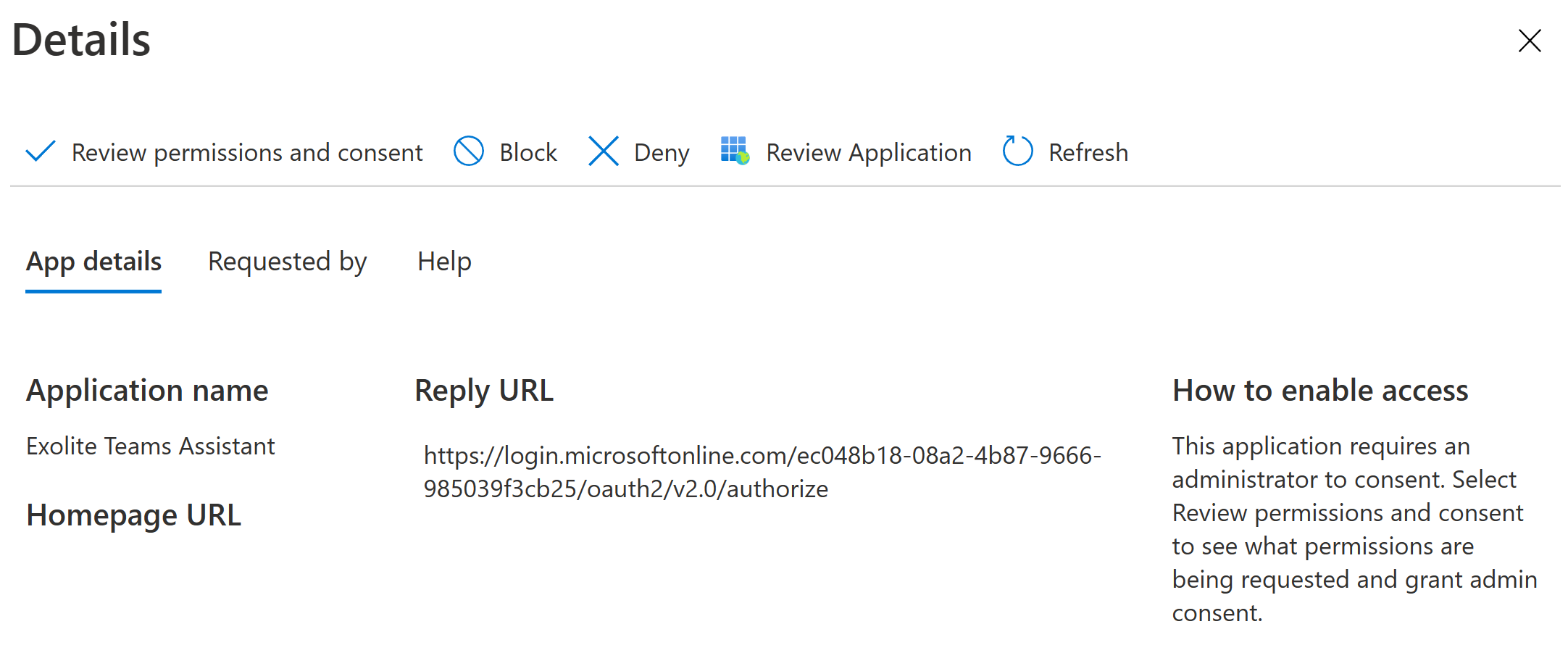

A reviewer either selects the Review request link in the email or navigates manually to Enterprise Applications > Admin consent requests. They can then select the desired pending app consent review to take a closer look.

In the details pane, the reviewer can check data points such as the justification given by the user, the reply URL of the app (where the app would point the user to) and the homepage URL designated for the app. The reviewer can also choose to see the exact permissions requested by the app with the Review permissions and consent button.

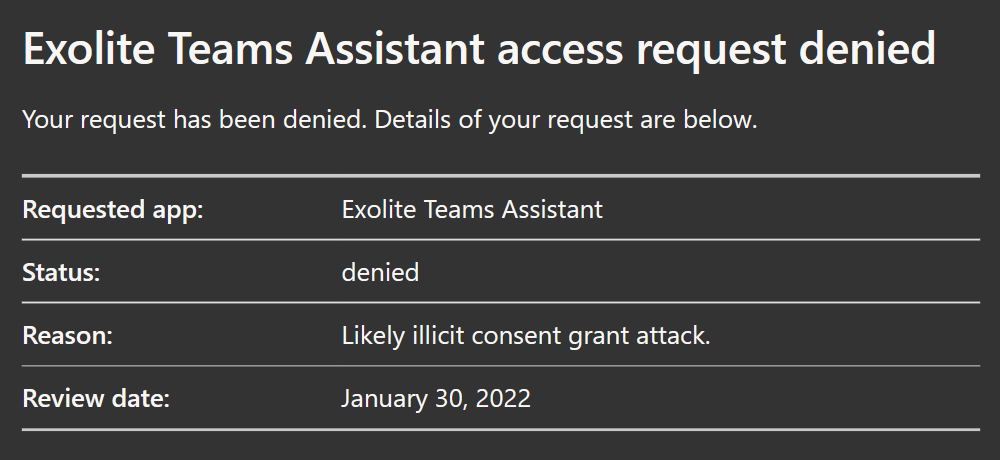

On reviewing the requested permissions and after ascertaining that no such app has in fact been produced by the company, the reviewer not only does not give consent to the app but chooses to block it as a likely illicit consent grant attack attempt.

Blocking an app bars users from interacting with or accessing it in your tenant, effectively shutting it down until further action is taken. The reviewer has to provide a reason for the block for logging purposes and after doing so, is allowed to proceed with blocking the app from further consent requests.

As for Joe, he isn’t left wondering and promptly receives an automatic email informing him of the decision and reasoning provided by the reviewer. This handily removes the need to manually communicate review decisions to the requestor, saving time and energy and helps give reviews more weight.

With both the limitation of user consent to low-risk permissions and the admin consent request workflow implemented, the easiest avenue for illicit consent grant attacks is now in control.

Parting thoughts

I still suggest following Microsoft’s playbook and checking out the permissions people have already consented to before these controls were put in place.

It is also a good idea to take a look at OK’d multi-tenant production apps provided by third parties to make sure their developers aren’t lazily asking for overly-broad permissions instead of using the principle of least privilege.

In addition to Microsoft solutions like Defender for Cloud Apps (integrated with Sentinel if possible), there are plenty of community- and Microsoft-produced tools that help you understand and manage app permission consents, such as:

- Sentinel KQL query to identify unused service principals with *.All permissions

- Sentinel KQL query to gather newly granted permissions into an array

- List all delegated and app permission grants with PowerShell

Stay safe out there!